In November 2015, animal welfare organisations SAFE and Farmwatch called on New Zealand and international consumers to ditch milk consumption, following their investigation into animal cruelty in the New Zealand dairy industry. The investigation revealed what they saw to be inherent cruelty and showed clear, deliberate abuse of baby calves. The SAFE footage revealed “cows running after their babies as they are taken away from them when only a few hours old, 4-day-old calves left in crates at the side of the road for up to eight hours, despite the law requiring them to be fed two hours before transportation, drivers throwing calves into the back of trucks, dead calves thrown into piles at farm gates, a slaughterman kicking and throwing calves before bashing them on the head and eventually slitting their throats.”

The SAFE website reveals the objective of their hidden camera investigation:

“For the sake of milk products, every year the New Zealand dairy industry treats millions of 4-day-old calves as ‘waste products’, tearing them away from their mothers and sending them to the slaughterhouse. Even when no laws are broken, these calves never even have a chance at life. By bringing public attention to the cruelty, we will force the industry to set higher standards and improve the treatment of bobby calves. We also want the government to separate animal welfare from the Ministry for Primary Industries and allocate sufficient funding to enforce the law.”

Dairy farmers are unhappy about SAFE’s international campaign describing their products as “contaminated by cruelty”, which they say distorts the reality of their industry. As a result more than 6000 Kiwis signed a petition to revoke SAFE’s charitable status, and a countermeasure Facebook page emerged on behalf of betrayed farmers, aimed at showing the real side of farming, “the love and dedication we show to our animals”.

“They [SAFE] are damaging our dairy industry. That is obviously what their intention is.” said West Coast dairy farmer Renee Rooney, who also described the campaign as ‘emotional scaremongering.’

The SAFE and Farmwatch investigation aired on TV One programme Sunday on the 29th of November. Immediately, the The Ministry of Primary Industries was under a lot of pressure to do something about the negative publicity. The slaughterhouse in question, Down Cow abattoir, was closed for good in 2016, and the slaughterman recorded abusing calves admitted his guilt in court. The Government also announced a string of changes to regulations surrounding bobby calves, but was criticised for having not a single animal rights group on the board making the decisions. Farmwatch also argued that there were already many regulations surrounding bobby calves before their investigation which didn’t prevent these abusive incidents from occurring.

For many of us, this was the first time we’d ever heard this normal, wholesome product being associated with cruelty and brutality. What we stirred into our tea every morning, mixed lovingly into cakes and treats – New Zealand’s biggest export earner – was under attack. Our long-trusted dairy industry was accused of severe animal abuse – and not only criticised for the minority cases which many farmers themselves would not tolerate: SAFE and Farmwatch believe dairying is an inherently cruel business.

This conclusion is based on the premise of an animal’s perceived right to bodily autonomy, and stresses the importance of animal welfare.

Animal welfare?

Protecting an animal’s welfare means providing for its physical and mental needs. Many consumers consciously wpurchase animal products which have assured them that the animal lived in humane, dignified conditions. Labels such as ‘free range’, ‘organic’ and ‘grass-fed’ give us this reassurance.

But it’s true that every person has different interpretations of the term animal welfare. Some think of companion animals abandoned by old minders and stuck in adoption shelters, some think of the lions and monkeys behind metal bars in zoos, or the cruel treatment of performance animals in circuses and aquariums. Some picture the faces peering out of cattle trucks, pigs in dirty gestation crates unable to turn around. But to associate milk with animal cruelty? Well, that’s a new concept.

This is not to say that animal welfare is not controlled or considered in dairying. In our primary industries, animals are meant to be protected by the The Animal Welfare Act 1999, which is a part of the New Zealand legislation which sets out the responsibilities of people who keep animals for any reason. It sets out offenses and penalties and gives legal authority to the Minimum Standards contained in Codes of Welfare. Sections 10 to 14 of the Animal Welfare Act 1999 set out the principle obligations and offenses relating to the keeping of animals in New Zealand. These include:

Not keeping animals alive in unnecessary pain or distress.

Not selling an animal in pain/distress unless it is to be killed.

Not deserting an animal without providing for its needs.

Not ill-treating an animal or killing it in such a way that it feels unnecessary pain/distress.

Ensuring sick/injured animals are treated to relieve pain/suffering, or are humanely killed instead.

I wanted to see whether the said humane process of milk production within the law, actually aligns with the key responsibilities farmers have in order to achieve true welfare of a herd. With help from the Dairy NZ website and stuff.co.nz, I was able to outline what appears to be standard practice in New Zealand dairying.

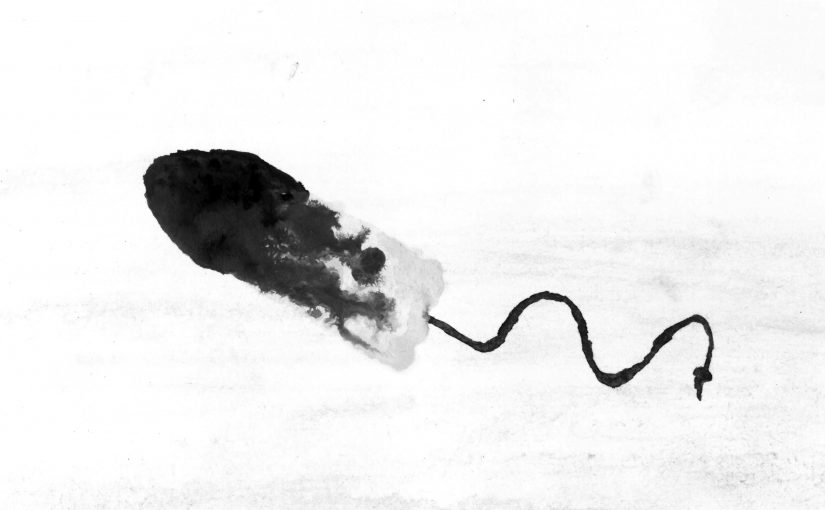

A mammal has to be pregnant to produce milk. To impregnate female cows, farmers use artificial insemination methods, involving instruments or a human hand to do so, with bulls are used to finish the breeding season. The cow carries her young for nine months like a human being. After birth, New Zealand farming allows around 72 hours before they separate the mother from her calf, however farmers do choose to interfere earlier because the longer the mother bonds with her young, the more distressing the separation can be for both parties.

SAFE and animal liberation organisations such as PETA and the Vegan Society of Aoatearoa insist that the emotional toll this practice has on the mother and her young is extensive due to their ability to mourn the close bond they develop for one another.

On the other hand, dairy farmers say keeping calves on their mothers would be massively impractical and that separation is a basic element of dairy farming. It is said that keeping calves with their mothers would create massive logistical issues for farmers during twice-daily milking, and in fact, bringing a lot of calves into a yard full of cows is said to be a big welfare issue. The calves would drink the milk produced by their mothers, leaving less to be sold and decreasing farm profitability.

We now arrive at the disposal of male calves. A bobby calf is an unweaned calf at least four days old and one that is killed for human or pet food consumption. Most bobby calves are bulls which are not wanted because they do not provide milk or are not suitable for becoming beef cattle. Because of this there is little money in bobby calves, and thus another industry is created out of these accidents of birth: the veal industry.

SAFE’s argument says these are fragile, vulnerable beings, often weak from lack of food and the long journey to the slaughterhouse, and that although bobby calves must be at least four days old and in good condition before being sent to slaughter, some dairy farmers still present weak and listless calves, so young they still have wet navels. Hence, their statement that even when treated inside the regulations of animal welfare, these bobby calves still ‘never even have a chance at life’.

The female newborns deemed healthy endure the same fate as their mothers, and are impregnated as soon as possible. Dairy cows are kept in a continuous process of artificial impregnation, gestation, calf separation and mechanised milking until their bodies are considered physically ‘spent’. Around a quarter of New Zealand dairy cows suffer from mastitis at some time in their lives. Symptoms include hot, swollen, acutely painful udders, fever, and loss of appetite. Severe cases of mastitis can kill a cow in 24 hours. After about five years of this repetitive process, cows’ milk production drops off and they are slaughtered for meat. However some cows don’t make it to five years, because they are slaughtered earlier if their milk production falls, or if they fail to become pregnant. Although dairy cows are slaughtered around age 4, their natural lifespan without human interference is 15-20 years. Up to a million young dairy calves are slaughtered every year in New Zealand.

If the welfare act is supposed to protect animals from being kept in unnecessary pain or distress, from a human failing to provide for their needs, from desertion and ill treatment, is the standard process of milk production, from artificially inseminating animals, taking their young away, appropriating the milk intended for their young for our own use and commercially slaughtering them for meat, not a complete violation of the act, and of animal welfare in general?

Do cows really feel pain?

There’s no question about whether a cow does or does not experience the forms of pain, grief and trauma SAFE implies; humans are not exceptional nor alone in the area of sentience. It is an anthropocentric view that only big-brained animals like great apes, elephants, cetaceans and human beings have the sufficient capacity for complex forms of sentience and levels of consciousness. Scientifically, farmed animals, just as much as cats and dogs, desire to live simply in peace and safety, absent from fear, pain or suffering.

Animal behaviorists have found that cows interact in complex ways, developing friendships over time, sometimes holding grudges against cows who treat them badly and choosing leaders based upon intelligence. They experience complex emotions, and even have the ability to worry about the future. Like humans, they quickly learn to avoid things that cause pain, like electric fences. In fact, if just one cow in the herd is shocked by an electric fence, it’s likely the rest of the herd will learn from that and will avoid the fence in the future. Unfettered from humans, they are naturally gentle animals, who would live in small herds with a hierarchy, friendships and social interactions. A cow can recognise more than 100 members of her herd, and relationships are clearly important to them.

If we ever find ourselves wondering about the welfare of an animal, it means we acknowledge the degree to which cows and other farmed animals can suffer if treated badly; that they deserve to have their wellbeing considered, merely because they are sentient. The moral significance of animals lies not in their differences to the human species, or how they provide for us, but rather their commonalities with us as subjects of a sentient life.

Welfare vs. rights

Any time we make a living being into a machine, a supplier of inventory, the bottom line will always be profit. When profit is king, society has to maintain a separation from personal values and products of a living origin. As long as we don’t seek to know them or their experiences, the animals on farms have no names, no faces, no identities. And as long as they remain inventory numbers, their suffering is non-existent. Perhaps ‘head-in-the-sand’ mentality is a result of society collectively failing to individualise farm animals from the beginning.

My question is: have the welfare of a being, and the rights of a being, become blurred concepts? Does it really matter how well a being was treated if their entire lives from birth, reproduction, and ultimate death was designed, managed and planned by a human? Does it matter how well they’re cared for, if from the day they are born, someone else has already planned their execution?

That to me, is the difference between welfare and rights. The Welfare camp believes exploitation can be done through humane treatment, and the Rights camp rejects the concept that there is an acceptable or humane way to exploit, use or slaughter an animal.

Speciesism?

There are numerous cultural and societal factors which come together to form our perception of animals, a conditioning that can be difficult to amend once we recognise it. When we are young, we are delighted by the cute farm animals in story books. We root for the animal to escape the farm in movies, relieved when Babe narrowly escapes his fate as Christmas dinner.

But as adults, the world is much more logical. We can get different animals to do and be different things for different human fulfillments; a dog is loyal to us, cats wise and comforting, rabbits compact and adorable, dolphins majestic and beautiful, cows… tasty and profitable.

Is this cognitive dissonance, society’s inconsistent thoughts, beliefs and attitudes toward certain animals, based solely on an animal’s cute factor or what they can do for us? Or is it based on an animal’s ability to provide ideal domestic companionship? The answer isn’t black and white, and it may be because there hasn’t been a movement in the past which caused anyone to consider the hypocrisy in our attitudes.

Where does this leave us?

I decided to open with the story on our dairy industry, because the farming of animals is the backbone of New Zealand. Dairy and meat are the primary industries that support our economy, synonymous with good health and economic prosperity to the vast majority of our society. SAFE became some form of the devil-spawn for questioning the ethics of the industry, and cries of economic sabotage were expressed nationwide. It is interesting to me how the public’s reactions to this issue brought to the surface the different values we as consumers place on farm animals’ lives.

At the end of the day, many people are good people, animal-lovers with compassion, and when we have the vital information, we have the opportunity to fully align our thoughts with our behaviour, and vote for animal rights with our dollar. Today, it seems hard to visualise a future where human life is no longer dependent on animal suffering. If we decide to stop exploiting animals, our society will change fundamentally. Our daily lives may be affected in many ways, as we learn to relate to animals as sentient beings who are different to us, but who also experience pain and joy, fear and desire. While changing our behaviour seems difficult now, it may ultimately allow humans, as well as animals, to enjoy richer and fuller lives.

By Violet Rowe

Images attached to this article